Point of care testing (POCT), is comparable to laboratory testing for INR measurements with regards to the precision1-3 and accuracy3-6 of results and the clinical agreement in the VKA-dosing decision. 3,6,7

CoaguChek systems offer a holistic solution that can help you improve quality of care, patient satisfaction and workflow efficiency.

Article

Point of care INR testing

The benefits of point of care testing

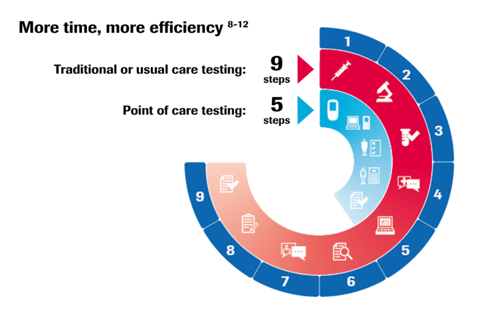

Streamline your workflow

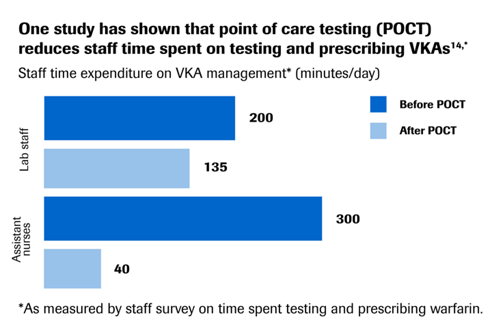

POCT can streamline anticoagulation management and improve workflow efficiency over usual care by providing:

- Shorter clinic visits13-15

- Reduced workload9,14

- Faster clinical decisions including immediate on-the-spot dose adjustment9,14,16,17

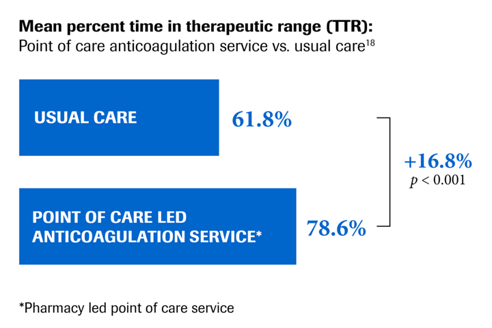

Improve patient care and satisfaction

Patients managed with POCT achieve a higher time in therapeutic range and fewer values out of range compared with patients treated with usual care.18-20

This results in:

- Fewer treatment-related complications9,21

- Fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits9,21

- Improved patient satisfaction13,22,23

Increase revenue and cut costs

Economic evaluations have shown that POCT is a cost-effective alternative to usual care24,25 and is associated with:

- Reduced clinic running costs14,22

- Increased revenue generation in some settings9

- Cost savings due to fewer hospitalizations and emergency department visits9,10

- The potential to reduce costs for the healthcare system24-26

Abbreviations

INR: International Normalized Ratio; VKA: vitamin K antagonist

References

- Bonar et al. (2015). Semin Thromb Hemost 41, 279–286

- Plesch et al. (2008). Thromb Res 123, 381–389.

- Christensen et al. (2012). J Thromb Haemost 10, 251–60

- Meneghelo et al. (2015). Int J Lab Hematol 37, 536–543

- Plesch et al. (2009). Int J Lab Hematol 31, 20–5

- Dillinger et al. (2016). Thromb Res 140, 66–72

- Colella et al. (2012). Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 23, 172–174

- Larsson et al. (2015). Ups J Med Sci 120, 1–10

- Wurster & Doran. (2006). Dis Manag 9, 201–209

- Rudd & Dier. (2010). Pharmacotherapy 30, 330–338

- Shaw et al. (2014). Int J Pharm Pract 22, 397–406

- Gubala et al. (2012). Anal Chem 84, 487–515

- Kong et al. (2008). Ann Hematol 87, 905–910

- Fernholm & Hermansson. (2015). BMJ Qual Improv Rep 4, pii: u208905.w3692

- Kasinathan et al. (2016). OALib J 3, e242281

- Smith et al. (2012). Am J Med Sci 344, 289–293

- Richter et al. (2016). Ann Pharmacother 50, 645–648

- Harrison et al. (2015). Int J Pharm Pract 23, 173-181

- Okuyama et al. (2014). Circ J 78, 1342–1348

- Mearns et al. (2014). Thromb J 12, 14

- Karlsson (2016). BMJ Qual Improv Rep 5, pii: u211003.w4421

- Chan et al. (2006). Br J Clin Pharmacol 62, 601–609

- Thompson et al. (2009). Pharm Pract (Granada) 7, 213–217

- Health Quality Ontario. (2009). Ont Health Technol Assess Ser 9, 1–114

- Claes et al. (2006). Value Health 9, 369–376

- Gerkens et al. (2012). J Thromb Thrombolysis 34, 300–309